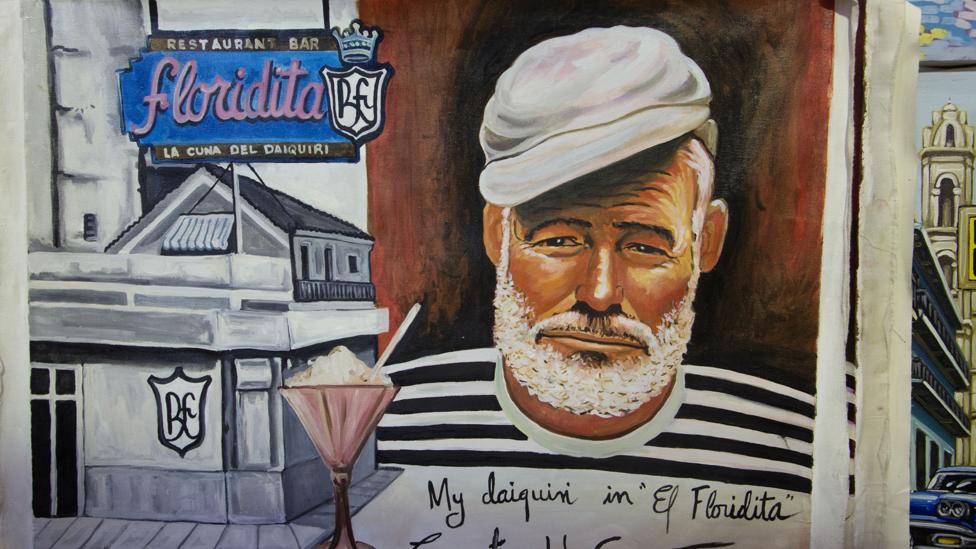

He was famous for his constant womanizing, his achingly cool moustache and his affection forsix-toed cats. Legend has it that he could drink25 daiquirisin an afternoon, he wasrecruited by the KGB as a spycodenamed “Argo” and he onceslept with a bear. Oh, and he wrote some of the most highly acclaimed works of all time.

I’m talking about Ernest Hemingway, of course. But it turns out that the author had more than novels and macho anecdotes up his rugged, intellectual sleeves. He was also the inventor of a clever psychological trick: the “useful interruption”.

according to a 1574116725615 articleHemingway penned for Esquire magazine, when asked “How much should you write in a day?” By a young writer, he replied: “The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day when you are writing a novel, you will never be stuck. ”He urged the nascent writer to remember this – and even went so far as to say that it was the most valuable advice he could give.

But does it actually work?

Regrettably, Hemingway’s entreaty has largely been ignored, and today his best-remembered nuggets of wisdom are those which fit more neatly on fridge magnets, like “courage is grace under pressure” ( it really is).

Or at least that was the case, until Yoshinori Oyama heard about Hemingway’s strategy in (****************************************. The researcher from Japan’s Chiba University was sitting in a café, catching up with a friend, when he had a thought: in his own life, he was much more motivated to get back to tasks if he had left them when they were going well. “My friend was like‘ Oh, Hemingway used to do this! ’,” He says.

Oyama wondered whether this strategy might be useful for other people, too. Around a year later, he roped in Emmanuel Manalo from Kyoto University, and

the pair set to work finding out.

Harnessing optimism**********

The basic premise behind the study was that not finishing a task can be beneficial. However, the researchers decided there was no need to restrict this gift from Hemingway to writers alone – and suggested that the rules could be broadened to help with this. Instead of just having a vision of the direction your work is heading in, they took the liberty of adding two more principles: people should feel that they are close to finishing the task, and it should be challenging enough so that you care if you complete it or not.

There were two parts to the study. For part one, Oyama asked 260 undergraduate students in his classes to complete a laborious task, which involved copying out text from newspaper columns by hand, into a kind of squared paper called a writing grid. Before they started, they were surveyed about how motivated they felt.

As soon as the first few students started to put up their hands to say they had finished, Oyama asked the rest to stop. Then the students were asked to count how many characters they had left to copy and quizzed about how compelled they felt to complete the task. As the researchers expected, the students who had less text left to copy were significantly more motivated to get back into it than those who had more left to do or – oddly – even those who had actually finished their work. Why?

Manalo believes optimism is a key factor. “We need to have belief in ourselves – some kind of expectation that we can do something. And when we’re closer to finishing something that we had previously failed to achieve, then that optimism increases. ”

Another factor is based on a school of thought cooked up by some Austrian and German psychologists in the early********************************** th Century called “gestaltism”. They believed that people made sense of the world by seeking out patterns, so the whole picture was more important to us than its individual parts.

“When we have parts of something, we always want to create a whole,” says Manalo. For example, if you show someone the outline of a triangle made up of broken-up dashes, our brains will automatically fill them in and assume it’s a picture of a triangle rather than a picture made of lots of lines.

“That’s the same thing that’s in action here, that we tend to want to complete something, especially if it’s close to making sense or close to achieving some sort of goal, ”says Manalo.

While part one of the study appeared to back up Hemingway’s theory, copying out text is hardly the kind of task that most people do regularly, so the researchers decided to check if the results would also work in more everyday scenarios. They wanted to see if the technique works best if you’ve already planned out what tasks lie ahead of you so that you can gauge how much work is left.

The researchers split a class of 549 students into two groups, and asked them to write about their memories from kindergarten to high school (from when they were four to 20 years of age) – a mammoth task. In group one, they were given help structuring their answers; they were told to split their memories into two parts, kindergarten to elementary school, and junior high school to high school. The others were given no such help. Before they started, the students were asked how motivated they felt.

Again, once most of the students were close to finishing the task, everyone was asked to stop. They were asked how close they were to completing it and how motivated they felt to continue. As previously, the students who were the closest to finishing felt the most motivated. But this time another effect emerged – crucially, those who were asked to divide the task in two, and consequently might have found it easier to gauge how much time they had left, were also more interested in getting back into it.

Task, interrupted**********

Task, interrupted**********

The results fit neatly with the research of Daniella Kupor from Boston University who looked into the effects of interruptions in (*******************************************. For one study, Kupor and colleagues from Stanford and Yale universities asked people to watch a short clip in which a comedian relayed a childhood anecdote. Half were allowed to watch the joke to its climax, while the others were left hanging.

Next the participants were asked to do some imaginary online shopping, for a seemingly unrelated study. They were told what to look for, and then presented with two potential purchases, which may or may not fit the bill. When asked, those who had been interrupted in the previous study were significantly more likely to commit to buying something, rather than keep looking.

“When an interruption prevents individuals from achieving a particular goal or task, we find that they make faster and less thoughtful decisions in completely unrelated areas,” says Kupor. “They feel a lack of closure, and the resulting unsatisfied need for closure can spill over onto unrelated decisions – and motivate people to obtain it with those unrelated decisions.”

Kupor’s study indicates that interruptions can provide a motivational boost, but hints that it may not always be beneficial. For one thing, research – and common sense – suggests that we’re more likely to regret our decisions if wehaven ‘ t thought them throughproperly.

However, it could be that the Hemingway effect needs different conditions to manifest in a beneficial way. After all, the interruptions in Kupor’s study were in the middle of the task, and the phenomenon is all about timing; no one is suggesting that being accosted at your desk 10 times a day by an ultra-sociable colleague is going to do you any favors. To harness the effect properly, the interruption should be scheduled for when you feel like you know where you’re going with your work.

“Gestaltism” is a school of psychology stating that people perceive the world in large patterns and value the bigger picture more than its individual parts ( Credit: Alamy)

Either way, perhaps this strategy should be wielded with caution until we understand more about how stopping short of finishing tasks can affect our psychology.

Oyama and Manalo are more optimistic. They think the Hemingway effect could be harnessed to achieve any goal, no matter how big or small, and suggest it could be particularly useful in the workplace and in education.

Oyama already uses the strategy when he’s working on scientific papers, and the researchers are currently working on a study to see if it could help students finish their PhDs; Currently up to a third of students in Europe still haven’t finished writing up their research after a staggering six years. The idea is that by helping students to split up their work, the Hemingway effect will kick in as they approach the end of each section.

staggering six years. The idea is that by helping students to split up their work, the Hemingway effect will kick in as they approach the end of each section.

They also think their research could help people with everyday tasks, like grasping a new concept in school. “In classrooms, for example, sometimes teachers stop students when they’re struggling with something – they’ll say, OK, we’ve had enough of that, let’s just continue this tomorrow. But that’s such a bad idea, ”says Manalo.

Though Hemingway suggested that useful interruptions should be self-imposed, the researchers are more concerned with the fact that the task is left unfinished than why or how this is the case. They don’t see a reason why carefully managed interruptions that are inflicted upon us by others should be any less effective.

Given the fact that we all already want to drink like Hemingway, dress like him, write like him and style our homes with dubious furniture claiming to have something to do with him, maybe It’s about time we started to plan our work like him, too. After all, Hemingway explicitly told us to – and who are we to disobey?

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings