Go home researchers, you’re drunk –

They claimed men should stop drinking for 6 months. They didn’t study that. *******

(Enlarge)/Man sips a beer.

reduce the risk of having a baby with a congenital heart defect, men should avoid drinking alcohol for at least six months prior to fertilization. At least, that’s the claim that researchers made in a press release last week. It’s the same claim thatmultiplenews outlets dutifully parroted instartling headlinesand stories about the researchers’ study.

The problem is thatthe researchers’ studydoes (not) support that claim. In fact, the question of whether six dry months before fertilization could reduce the risk of congenital heart defectswasn’t addressedin the study. The researchers didn’t even have the data to know if any fathers abstained from alcohol for that long prior to helpingform a babby.

It seems that the now-widespread recommendation was merely the researchers’ personal opinions, which were oddly included in the press release and don’t appear to be based on any evidence from their study or otherwise.

What their study did examine was whether a father’s alcohol consumption within (Three) months before fertilization — or, mind-bogglingly, three monthsafterfertilization — could influence the risk of a congenital heart defect. The researchers concluded that dad’s drinking in that six-month time frame did have an effect; it raised the relative risk of a congenital heart defect by 44%. The authors speculate that alcohol could cause subtle changes to DNA in sperm that could then lead to that elevated risk.

But even the conclusions that are based on data are questionable. A closer look at the researchers ’analysis reveals many troubling weaknesses and caveats. For one thing, it’s unclear how a father’s sperm — alcohol-damaged or not — could have any effect on a fetusafterfertilization. The researchers also skim over the fact that men in their study who drank up to about 3.5 standard alcoholic drinks a day appeared to havelessrisk of fathering a child with a congenital heart defect than non-drinkers. And the researchers extended their risk assessment to fathers who might be drinking up to a whopping 500 grams of alcohol a day. Given thata standard alcoholic drink in the US contains 14 grams of alcohol, that’s nearly 36 drinks a day — alife-threatening amount of alcohol.

And that’s just the first sip of what’s in this mind-bending study. Let’s dive into the rest.

Tipsy start

The researchers have a wobbly explanation as to why they even carried out the study, which was publishedOctober 2 in theEuropean Journal of Preventive Cardiologyby a team at the Central South University in Hunan, China.

In the study’s introduction, the researchers first note that some earlier studies had suggested that children withfetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs)have an elevated risk of congenital heart defects (CHDs).

Worldwide, CHDs are the most common type of birth defects, withmany different subtypes of varying severity. In the US, about 1% of babies born each year have some form of a CHD,according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The cause of any given defect is often unknown.

After bringing up a link between FASDs and CHDs, the researchers go on to note that studies looking at the possible link between maternal drinking and CHD have yielded mixed findings. But, they add, there have been three, big meta-analysis studies in recent years looking into the issue. And all three found no statistically significant link between maternal drinking and CHDs.

Despite this, the authors say the question is still an open one and that no research to date has looked for a link between CHDs and alcohol use in fathers. But this is an odd set-up for the study, given that FASDs are a group of conditions defined specifically as those caused bymothers drinking during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, the researchers call for another round of analysis.

Messy methods

For their fresh pour, the researchers conducted a fourth meta-analysis, one that included new studies that weren’t in the past analyzes. Generally, meta-analyses are studies that harvest and repurpose data sets from many other studies — sometimes data that’s been published, sometimes not— using them to try to answer new questions. In this case, the researchers could sift through any studies with data on birth defects that also included data on various lifestyle factors of the babies’ parents. From there, they could pull out data specifically on CHDs as well as any survey questions about parental alcohol use that just happened to be included.

The strength of these types of analyzes is that they can amass data from many smaller studies into one big one, potentially firming up conclusions with larger numbers and mightier statistics. But this can also create many problems. For one thing, smashing together data from different studies can obscure any poor-quality data that’s included. There’s also the larger issue of publication bias — a tendency to publish the studies that find links over the ones that don’t. And by nature, meta-analyses can combine studies that may have disparate study designs, methods, and statistics.

In this meta-analysis, some of the harvested data only related to certain subtypes of CHDs. The included studies asked parents slightly different questions about when, how much, and how often they drank around the time of a pregnancy. The studies also have differences in how they refined their data — such as trying to account for known risks of having a child with a CHD, such as a family history or certain medical conditions.

Still, even if the researchers had managed to stumble passed all these problems, at best, the study can only point out a correlation between parental drinking and CHDs. It can’t determine if drinkingcausesCHDs. Moreover, the heart of the data — parental alcohol use — is also based on survey responses, which can be unreliable because people may not accurately report (or admit) how much they really drink.

Drunk data

Given all these limitations, the researchers boldly conclude that “[w] ith an increase in parental alcohol consumption, the risk of CHDs in offspring also gradually increased. Therefore, our findings highlight the necessity of improving health awareness to prevent alcohol exposure during the preconception and conception periods. ”But the data is far less steady.

Jiabi Qin, included data from 55 studies in their meta-analysis, amassing data on nearly 42, 00 0 babies with CHDs. But only 24 of those studies included any data on paternal alcohol consumption, and only nine included data on fathers who reported binge drinking (defined as having five or more alcoholic drinks in one sitting).

Overall, they found that mothers who reported any drinking in the three months before or three months after conception had a 16% higher risk of having a baby with a CHD than non-drinking mothers. Fathers who drank had a 44% higher risk.

But when they broke down that link to specific types of CHDs, only maternal drinking was statistically significantly linked to a higher risk of just one of the types of CHD — calledtetralogy of Fallot, which is a rare CHD that leads to low oxygen levels in the blood.

The authors note: “our study did not find a statistically significant association between parental alcohol exposure and the remaining phenotypes of CHDs because of the limited number of included studies for specific phenotypes. ”

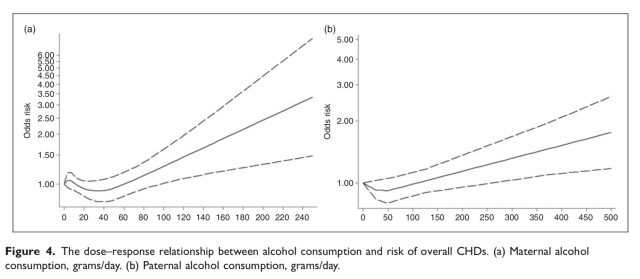

When the researchers spilled their data into dose-response charts, the link between drinking and CHDs was even more watered down. Dose-response charts aim to look at how the dose of alcohol affects the risk of CHD. You might expect them to be in step with each other — that is, the more alcohol, the more risk.

Enlarge/The dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of overall CHDs. (a) Maternal alcohol consumption, grams / day. (b) Paternal alcohol consumption, grams / day.

Zhang et al.

But the relationship wasn’t in step. In fact, fathers who reported drinking up to 50 grams of alcohol per day (around 3.5 standard US drinks) seemed to have a lower risk of fathering a child with a CHD than non-drinkers (although this dip wasn’t statistically significant). At that 50 grams per day point, the risk of CHD starts to increase. When fathers drink over 100 grams per day (around seven standard US drinks a day), they start seeing elevated risks of CHD compared with non-drinkers.

The researchers extended their dose-response curve out to fathers who might drink a shocking 500 ga day, an equivalent of nearly 36 standard US drinks a day.By one calculation, a (- pound) 91 kg) man who drank (beers) 12 – ounces each, 5% alcohol (over a full) – hour period would have an estimated blood alcohol content (BAC) of about 0. 45%. The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism considers any BACover 0. 31% to be life-threatening, potentially causing loss of consciousness and “suppression of vital life functions.” In other words, that amount of alcohol is not compatible with your own life, let alonetrying to create a new one.

Sobering up

Given all the data, the researchers may have found a real link between paternal alcohol use and CHDs, but the finding will need to be verified and refined in yet more studies. And whether paternal alcohol use directly causes those defects will have to be explored in even more studies. For now, it’s still too early to draw any clear public health recommendations from this meta-analysis (except, obviously, don’t drink 500 grams of alcohol in a day).

Still, that didn’t seem to stop lead author Qin from overstating the findings. Astupefying press releasecirculated by the European Society of Cardiology notes: “Dr Qin said the results suggest that when couples are trying for a baby, men should not consume alcohol for at least six months before fertilization while women should stop alcohol one year before and avoid it while pregnant. ”

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings