not that private –

Most users opted not to share data with police, who still got it all anyway.

Kate Cox –

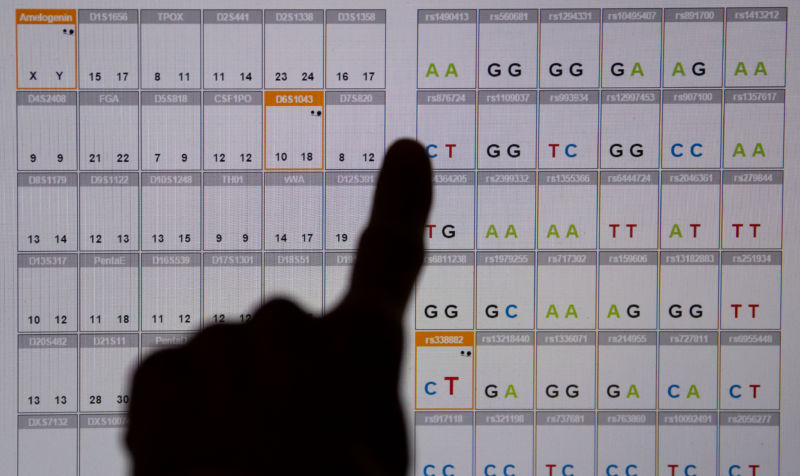

Enlarge/A DNA sequence analysis (genetic fingerprint) seen on a monitor in the Bavarian State Criminal Police Office in Munich, Germany.

Law enforcement agencies around the country have for the past few years eagerly latched onto consumer-facing DNA sites as a rich repository of information to help them close cases. Many of those sites have been allowing users to adopt privacy settings and restricting what data they allow police to access, but a first-of-its-kind search warrant may blow those users’ data banks wide open.

Police in Orlando, Florida, obtained a warrant this summer to search DNA site GEDmatch and review data on all of its users— about a million people,The New York Times reports. Privacy advocates are now concerned that police will continue to get broad warrants for DNA sites, including larger peers such as 23 andme or Ancestry that have much larger pools of user data.

GEDmatch? Sounds familiar …

GEDmatch hit the spotlight in 2018, when DNA data from its site led to the eventual arrest of a man suspected to be the “Golden State Killer, “responsible for dozens of rapes and murders in California between 1976 and 1986.

“Although we were not approached by law enforcement or anyone else about this case or about the DNA, it has always been GEDmatch’s policy to inform users that the database could be used for other uses, as set forth in the Site Policy, “site co-founder Curtis Rogerstold Arsat the time. “It is important that GEDmatch participants understand the possible uses of their DNA, including information of relatives that have committed crimes or were victims of crimes,” he added, saying that anyone not comfortable with that should delete their data from the site.

In the wake of that attention-grabbing case, GEDmatchchanged its policiesin May 2018 to make it less easy for police to access their data. Users now have to opt in to having their data made available to police; information they upload is set to private by default. Rogers told the NYT that as of October, less than 15% of current users, 185, 00 0 out of 1.3 million, have opted in to share their data with police.

That limitation has frustrated law enforcement, though, and the Orlando detective in July asked a Florida judge to approve a warrant that would let him search the entire GEDmatch database regardless of users’ privacy settings, and the judge agreed. The site reportedly complied to the search demand within 24 hours.

Who generates the data?

GEDmatch, unlike its larger rivals, doesn’t collect any DNA data itself. Instead, it relies on user uploads. In itsterms of service, the company says acceptable data includes:

(Your DNA)

- DNA of a person for whom you are a legal guardian

- DNA of a person who has granted you specific authorization to upload their DNA to GEDmatch

- DNA of a person known by you to be deceased

- DNA obtained and authorized by law enforcement to identify a perpetrator of a violent crime against another individual, where ‘violent crime’ is defined as murder, nonnegligent manslaughter, aggravated rape, robbery, or aggravated assault

- DNA obtained and authorized by law enforcement to identify remains of a deceased individual

- An artificial DNA kit (if and only if: (1) it is intended for research purposes; and (2) it is not used to identify anyone in the GEDmatch database)

- DNA obtained from an artifact (if and only if: (1 ) you have a reasonable belief that the Raw Data is DNA from a previous owner or user of the artifact rather than from a living individual; and (2) that previous owner or user of the artifact is known to you to be deceased)

That openness is why investigators prefer to use GEDmatch, the Times explains. That differentiates it from the larger services, 23 andme and Ancestry, which perform DNA analysis themselves on samples that users send in.

23 andme this week in acorporate blog postreiterated its commitment to user privacy.

“If we had received a warrant, we would use every legal remedy possible” to challenge it and try to avoid turning over user data, the company’s chief legal and regulatory officer, Kathy Hibbs, wrote. “In our 13 year history, 23 andMe has never turned over any customer data to law enforcement or any other government agency. “

According to itstransparency report, since 2015, 23 andme has received seven requests pertaining to 10 individuals and has shared data in response to none of them.

The weakest links

With DNA, arguably more than any other kind of data, your privacy is only as assured as your least privacy-minded relative wants it to be — and you might not even know that person. Thousands of users have discovered surprise half-siblings, unknown biological parents, or forgotten branches of their family trees out there in the world since services like 23 andme became broadly popular.

Researchers in late 2018 found thatabout 60% of DNA samplesfrom a consumer genealogy company could be linked to distant relatives. That number went up for users of white European descent, who were 30% more likely to be matched because the user base of the testing platform skews toward higher -income white consumers.

GEDmatch, meanwhile, seems to be an even riskier repository for all that sensitive data than some of its competitors. It has no hesitancy complying with search requests. “We may disclose your raw data, personal information, and / or Genealogy Data if it is necessary to comply with a legal obligation such as a subpoena or warrant,” the site’s privacy policy says. “We will attempt to alert you to this disclosure of your Raw Data, personal information, and / or Genealogy Data, unless notification is prohibited under law.”

GEDmatch also has flaws in it that could allow a whole lot of unintentional access to genetic data, the MIT Technology Reviewrecently reported. The site has apparently been subject to data scraping attempts which might constitute a national security threat, the report explains.

Rogers downplayed the risks, answering, “I don’t want to get into it,” when pressed about the data scraping .

“We certainly are concerned about privacy also, and it’s good that studies like this are done,” Rogers added in a statement to the Technology Review. “But no matter what you do, there will always be some potential for privacy invasion when you are doing genealogy. Genealogy is a procedure in which you want to compare your information to other people’s.”

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings