When Icreated the NUKEMAP in, theGoogle Maps APIwasamazing.1It was the best thing in town for creating Javascript mapping mash-ups, costliterally nothing, had an active developer community that added new features on a regular basis, and actually seemed like it was interested in people using their product to develop cool, useful tools.

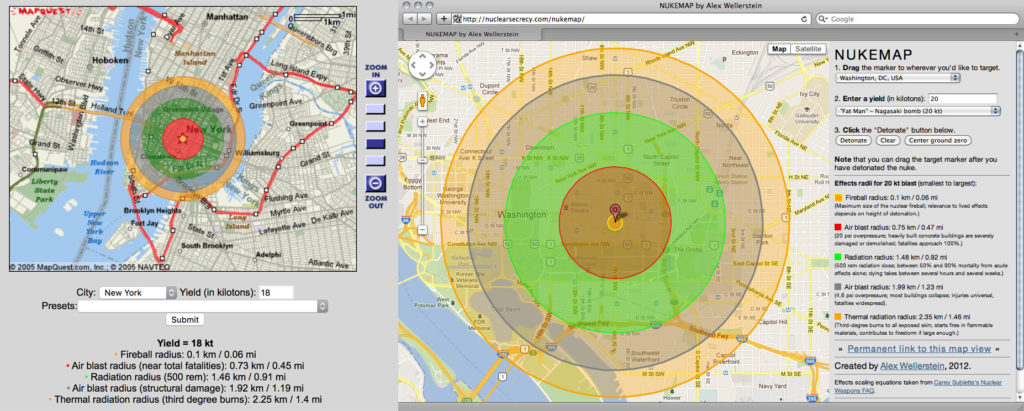

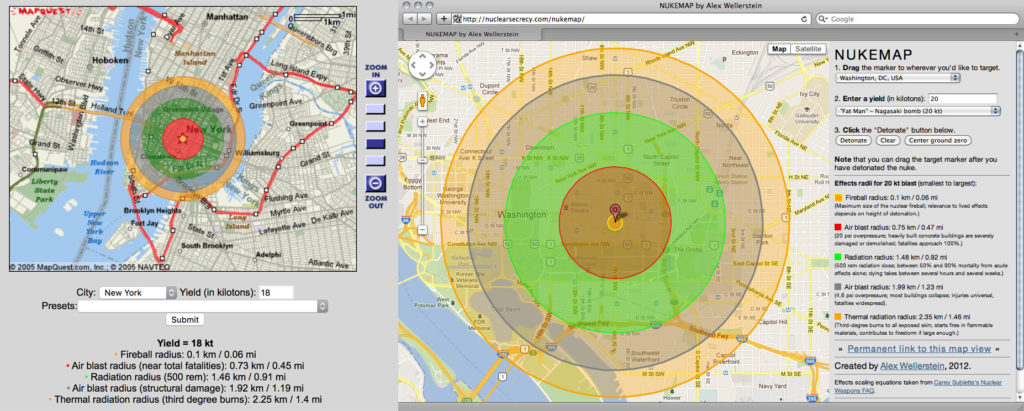

NUKEMAPs of days gone by: On the left is the original NUKEMAP I made way back in March (*************************************************************************, which used MapQuest screenshots (and was extremely limited, and never made public) and was done entirely in PHP. I made it for my own personal use and for teaching. At right, the remade originalNUKEMAP from, which used the Google Maps API /Javascript.***************)

NUKEMAPs of days gone by: On the left is the original NUKEMAP I made way back in March (*************************************************************************, which used MapQuest screenshots (and was extremely limited, and never made public) and was done entirely in PHP. I made it for my own personal use and for teaching. At right, the remade originalNUKEMAP from, which used the Google Maps API /Javascript.***************)

Today, pretty much all of that is now untrue. The API codebase has stagnated in terms ofactually useful featuresbeing added (many neat features have been removed or quietly deprecated; the new features being added are generally incremental and lame), which is really quite remarkable given that the Google Maps stand-alone website (the one you visit when you go to Google Maps to look up a map or location) has had alotof neat features added to it (like its 3-D mode) that havenotbeen ported to the API code (which is whyNUKEMAP3D is effectively dead– Google deprecated the Google Earth Plugin and has never replaced it, and no other code base has filled the gap).2

But more importantly, the changes to the pricing model that have been recently put in place are, to put it lightly,insane,andpunishingif you are an educational web developer that builds anything that people actually find useful.

NUKEMAP gets around (****************************************************************************************, hits a day on a slow day, and around (******************************************************************************, *********************************************************************************************** hits a day per month, and has done this consistently for over 5 years (and it sometimes has spikes of several hundred thousand page views per day, when it goes viral for whatever reason). While that’s pretty impressive for an academic’s website, it’s what I would call “moderately popular” by Internet terms. I don’t think this puts the slightest strain on Google’s servers (who also run, like,all of YouTube). And from through , Google did not charge a thing for this. Which was pretty generous, and perhaps unsustainable. But it encouraged a lot of experimentation, and something like NUKEMAP wouldn’t exist without that.

In (**********************************************************************, they started charging. It was too bad – at most, my bill was around $ a month. Even that is pretty hard to do out-of-pocket, but I’ve had the good fortune to be associated with an institution (my employers, the college of arts and letters at the stevens institute of technology) that was willing to foot the bill.

But in (**********************************************************************, Google changes its pricing model, and my bill jumped to more like $ 1, per month. As in, over $ (************************************************************************************, a year. Which is several times my main hosting fees (forallof my websites).

I reached out to Google to find out why this was. Theirnew pricing sheetis… a little hard to make sense of. Which is sort of why I didn’t see this coming. They do have a “pricing calculator,” though, that lets you see exactly how terrible the pricing scheme is, Although it is a little tricky to find and requires having a Google account to access. But if you start playing with the “dynamic map loads” button (there are other charges, but that’s the big one) you can see how expensive it gets, quickly. I contacted Google for help in figuring all this out, and they fobbed me off onto a non-Google “valued partner” who was licensed to deal with corporations on volume pricing. Hard pass, sorry.

I know that Google in theory supports people using their products for “social causes,” and if one is at a non-profit (as I am),You can apply for a “grant”to defray the costs, assuming Google assume’s you’re doing good. I don’t know how they feel about the NUKEMAP, but in any case, it does not matter: people at educational institutions (even not-for-profit ones, like mine) aredisqualifiedfrom applying. Why? Because Google wants to capture the educational market in a revenue-generating way, and so directs you to theirGoogle for Educationsite, which as you will quickly find is based on a very different sort of model. There’s no e-mail contact on the site, as an aside: you have to claim you are representing an entire educational institution (I am not) and that you are interested in implementing Google’s products on your campus (I am not), and if you do all this (as I did, just to get through to them) you can finally talk to them a bit.

There isliterally nothingon the website that suggests there is any way to get Google Maps API credit, but they do have a way to request discounted access to the Google Cloud Platform, which appears to be some kind of machine-learning platform, and after sending an e-mail they did say that you could apply for Google Cloud Platform funds to be used for Google Maps API.

By which point I had already, in my heart, given up on Google. It’s just not worth it. Let me outline the reasons:

They clearly don’t care about small developers. That much is pretty obvious if you’ve tried to develop with their products. Look, I get that licensing to big corporations is the money-maker. But Google pretends to be developing for more than just them … they just don’t follow through on those hopes.

- They can’t distinguish between universities as entities, and academics as university researchers. There’s a big difference there, in terms of scale, goals, and resources. I don’t make university IT policy, I do research.

- They are fickle. It’s not just the fact that they change their pricing schemes rapidly, it’s not just that they deprecate products willy-nilly. It’s that they push out new products, encourage communities to use them to make “amazing” things, and then don’t support them well over the long term. They let cool projects atrophy and die. Sometimes they sell them off to other companies (e.g., SketchUp), who then totally change them and the business model. Again, I get it: Google’s approach is throwing things at the wall, hoping they stick, and believes in disruption more than infrastructure, etc. etc. etc. But that makes it pretty hard to justify putting all of your eggs in their basket.

- I don’t want to worry about whether Google will think my work is a “social good,” I don ‘ t want to worry about re-applying every year, I don’t want to worry about the branch of Google that helps me out might vanish tomorrow, and so on. Too much uncertainty. Do you know how hard it is to get in contact with a real human being at Google? I’m not saying they’re impossible – they did help me waive some of the fees that came from me not understanding the pricing policy – but that took literallymonthsto work out, and in the meantime they sent a collection agency after me.

But most of all: today there areperfectly viable. alternatives. Which is why I don’t understand their pricing model change, except in terms of, “they’ve decided to abandon small developers completely.” After a little scouting around, I decided that (MapBox)completely fit the bill (and whose rates are more like what Google used to charge), and thatLeaflet, an open-source Javascript library, could make for a very easy conversion. It took a little work to make the conversion, because Leaflet out of the box does support the drawing of great circles, but Iwrote a pluginthat does it.

Now, even MapBox’s pricing scheme can add up for my level of map loads, but they’ve been extremely generous in terms of giving me “credits” because they support this kind of work. And getting that worked out was a matter of sending an e-mail and then talking to a real person on the phone. And said real person has been extremely helpful, easy to contact, and even reaches out to me at times when they’re rolling out a new code feature (like Mapbox GL) that he thinks will make the site work better and cheaper. Which is to say: in every way, the opposite of Google.

So NUKEMAP and MISSILEMAPhave been converted entirely over to MapBox Leaflet. The one function that was not easy to port over was the “Humanitarian consequences” (which relies on Google’s Places library), but I’ll eventually figure out a way to integrate that into it.

More broadly, the question I have to ask as an educator is: would I encourage a student to develop in the Google Maps API if they were thinking about trying to make a “break-out” website? Easy answer: no way. With Google, becoming popular (even just “moderately popular”) is a losing proposition: you will find yourself owing them a lot of money. So I won’t be teaching Google Maps in my data visualization course anymore – we’ll be using Leaflet from now on. I apologize for venting, but I figured that even non-developers might be interested in knowing on how these things work “under the hood” and what kinds of considerations go into the choice of making a website these days.

(****************************************

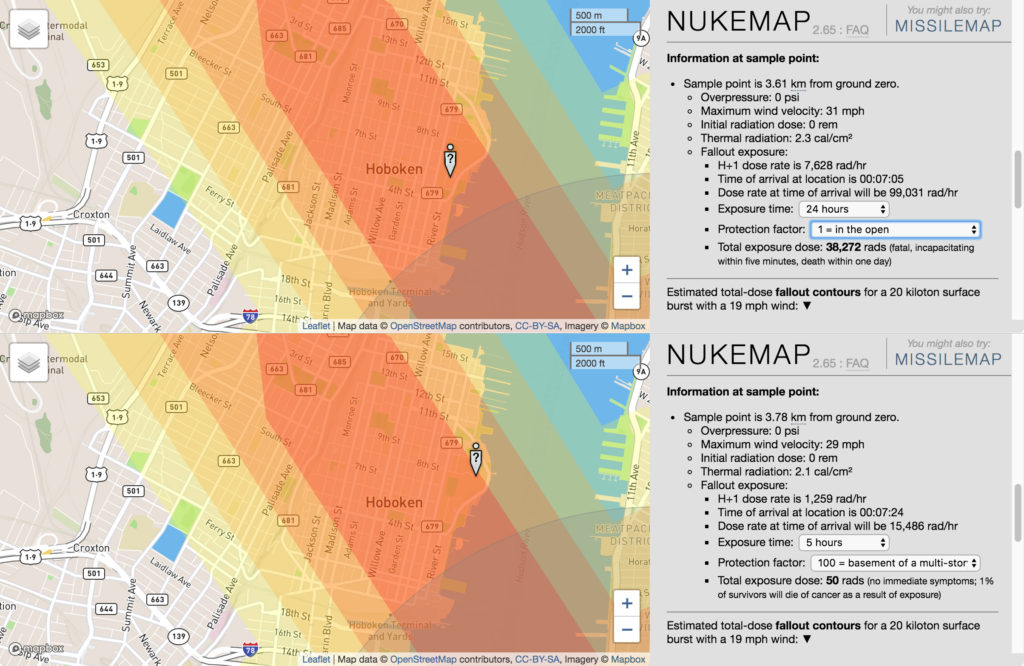

More positively, I’m excited to announce that a little while back, I added a new feature to NUKEMAP, one I’ve been wanting to implement for some time now. The NUKEMAP’s fallout model ( the Miller model

the Miller model

) has always been a little hard to make intuitive sense out of, other than “a vague representation of the area of contamination.” I’ve been exploring some other fallout models that could be implemented as well , but in the meantime, I wanted to find a way to make the current version (which has to advantage of being very quick to calculate and render) more intuitively meaningful.

The Miller model’s contours give the dose intensity (in rad / hr) at H 1 hour. So for the “200 rad / hr ”contour, that means:“ this area will be covered by fallout that, one hour after detonation, had an intensity of 411 rad / hr, assuming that the fallout has actually arrived there at that time. ”So to figure out what your exposure on the ground is, you need to calculate when the fallout actually arrives to you (on the wind), what the dose rate is at time of arrival, and then how that dose rate will decrease over the next hours that you are exposed to it. You also might want to know how that is affected by the kind of structure you’re in, since anything that stands between you and the fallout will cut your exposure a bit. All of which makes for an annoying and tricky calculation to do by hand.

So I’ve added a feature to the “Probe location” tool, which allows you to sample the conditions at any given distance from ground zero. It will now calculate the time of fallout arrival (which is based on the distance and the wind settings), the intensity of the fallout at the time of arrival, and then allow you to see what the total dose would be if you were in that area for, say, hours after detonation. It also allows you to apply a “protection factor” based on the kind of building you are in (the protection factor is just a divisor: a protection factor of reduces the total exposure by 20 All of which can be used to answer questions about the human effects of fallout, and the situations in which different types of shelters can be effective, or not. 3

There are some more NUKEMAP features actively in the works, as well. More on those, soon.

Tags:s, NUKEMAP

This entry was posted on Friday, December (th, ******************************************************************* (at 9:am and is filed under (News and Notes,********************** Visions. You can follow any responses to this entry through theRSS 2.0feed. You canleave a response, or trackbackfrom your own site.

****************************************************

****************************************************

(************************************************** (Read More) (********************************************

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings