Louise-Renée de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, is the subject of fifteen portraits in London’s National Portrait Gallery. She is alone in fourteen of them. Her curly hair, often parted to suggest that she’s not wearing a wig, is her defining feature. There is a wanton quality to how it’s arranged, lush and flowing even when it is carefully coiffed. In some of the portraits it seems as if the duchess, mistress to a king, has thrown on clothing only for modesty’s sake. Her expensive gowns and robes are simply draped over her shoulders rather than completely fastened and buttoned up. Born to a noble family in Brittany, she was one of Charles II’s mistresses but proved her loyalty to France by passing on information she gained in Charles ’courts back to Louis XIV’s.

In the one National Portrait Gallery painting where the duchess is not alone she stands next to a black child. A curatorial note suggests the little girl is primarily there as a status symbol. There are other paintings of the duchess at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, and scattered across other collections and galleries. It seems, however, that there is only one other painting where the duchess shares the frame.The Duchess of Portsmouth with an Attendant Carrying a Jewel Box, attributed to British portraitist Godfrey Kneller, currently hangs in philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah andNew Yorkereditorial director Henry Finder’s New York City apartment. The other figure in the painting, the attendant of its title, is also black and female.

Without the dress and pearls, the black child in the National Portrait Gallery painting might be mistaken for a boy. Her hair is cut close to her scalp, and there’s nothing delicate about her features. She looks quite young and has dark brown skin. Her face, turned up toward the duchess and smiling, is round. The green of her elegant dress complements the shrubbery just behind the duchess. Her single strand of pearls might, at first glance, seem incongruous — not just because she’s black but because she looks so young. Child figures dressed this opulently aren’t rare, but their style of dress is normally a sign not only of the class they were born into but of their future wealth as well. When we see little white girls of this period dressed this elegantly, we understand that they are adorned members of wealthy families, where they are being cultivated to participate in and contribute to the family’s wealth through marriage and the production of male heirs. The young black girl wearing the pearls, who is offering the duchess a piece of coral and pearls in a shell, is an object herself to be collected, owned, and displayed. The duchess has her arm around the girl and is looking at the viewer.

The attendant in the other painting is older than her National Portrait Gallery counterpart, on the cusp of womanhood. The space around her and the duchess is heavily draped, with only a patch of blue sky to suggest a world outside. The duchess leans on a pedestal; the attendant, slight and brown, stands next to her. Her dress is elegant and the same red hue as the ribbon in the duchess ’hair. Her ears are decked out in pearls. The rouge on the attendant’s cheeks is the same shade the woman next to her wears. Her hair covering is arranged in the same way as the duchess ’and adorned with a red jewel. Autumnal colors dominate the painting. Everything about the young black woman suggests that she is not only an “attendant” but an accessory and an extension of the duchess ’image. Their expressions are even similar. The attendant, however, is not looking directly at the duchess. She stares at a point beyond the viewer’s line of vision, and we have no clear indication where her gaze lands. Everyone I’ve asked about the focus of her gaze has a different opinion about where it is directed. Wherever the attendant is looking, her countenance does not show the same adoration present on the little black girl’s face in the National Portrait Gallery painting.

I first saw the painting of the duchess when I attended a benefit one spring evening in 2018 at Appiah and Finder’s home. Depending on where you are in the apartment, it’s possible to see the duchess without even knowing the attendant is there. I first saw the painting from such an angle, not noticing the attendant until later in the evening. Trying to figure out that gaze and her expression — serene rather than adoring — sent me back to look at the painting with questions for Appiah not about the painting’s central figure but about the young woman by her side.

In the past six years or so, I’ve become accustomed to seeing black figures in eighteenth – and nineteenth-century paintings in ways that countered my early training in art history, both in formal classes and in regular visits to museums and galleries. My art history education was more along the lines of H.W. Janson’sHistory of Art, which rarely included images of black people, than the multivolumeThe Image of the Black in Western Art. Figures like the attendant have made me reassess race and portraiture in art history, especially in the era literary scholars refer to as the Romantic period, which stretched from about 1790 to 1830.

Logistically speaking, this reexamination is an easier task now than it would have been even ten years ago with more art historians and critics, especially black ones, offering essential contexts and raising questions that move black figures from the margins to the center of art history, as in Charmaine A. Nelson’sRepresenting the Black Female Subject in Western Artand Simon Gikandi’sSlavery and the Culture of Taste. Kay Dian Kriz’sSlavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinementhas become a sort of bible, explaining the story behind paintings like Johann Zoffany’sThe Family of Sir William Young, which I first saw on the cover of the Oxford University Press edition of (Maria Edgeworth) ‘sBelindaI used in graduate school. The 1801 didactic novel tells the story of the rather uninspiring Belinda Portman’s adventures on the marriage market and the married women helping her sort through the tensions between duty and desire. The cover of the Oxford edition features a detail from the Zoffany painting of a black servant helping a white figure onto a horse, which reflect a thread in the narrative about the black servant of a West Indian suitor Belinda meets in the novel.

The cover was my first sign that the Romantic period was not as homogeneous as my professors had taught me in both college and graduate school. The Zoffany painting currently hangs in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, and the curatorial note in the museum is telling in what it elides. Young’s family is the subject of the painting, and he is described as having “interests” in the West Indies, a euphemism that refers to the sugar plantation he owned. His investment in slavery is made clearer on the museum’s website, which goes into some detail about Young’s participation in the slave trade. Something is still missing, however. Although every other figure in the painting is accounted for by name and relationship, both the vague note in the museum and the more explicit online version mention the black figure in the painting without offering any information about who he is. This in itself isn’t remarkable. Servants are rarely identified in paintings, whether they are white or people of color. Yet the black figure is acknowledged only as a signifier of Young’s “interests in the West Indies.” The absence of any information about him stung when I saw the painting in person this summer.

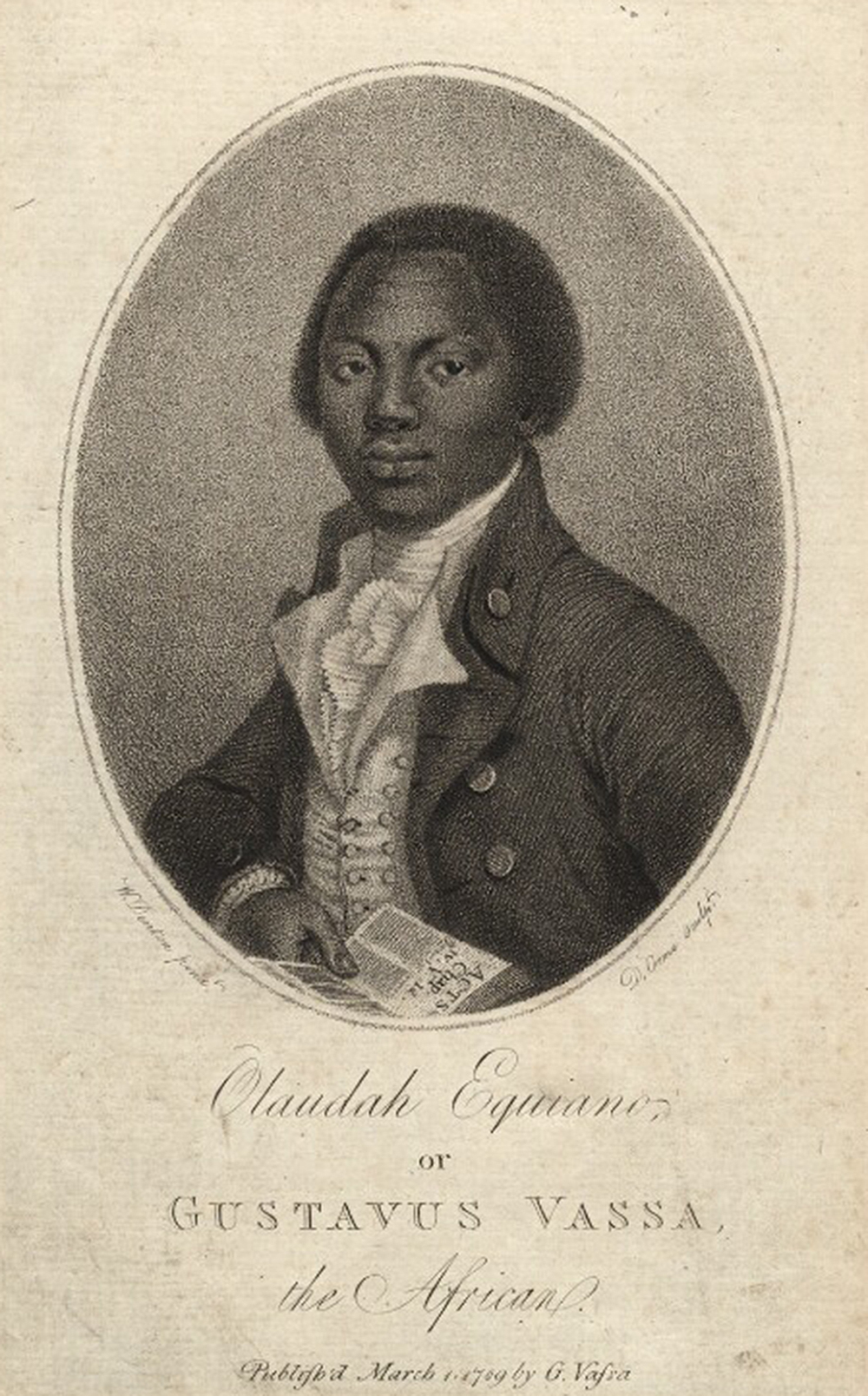

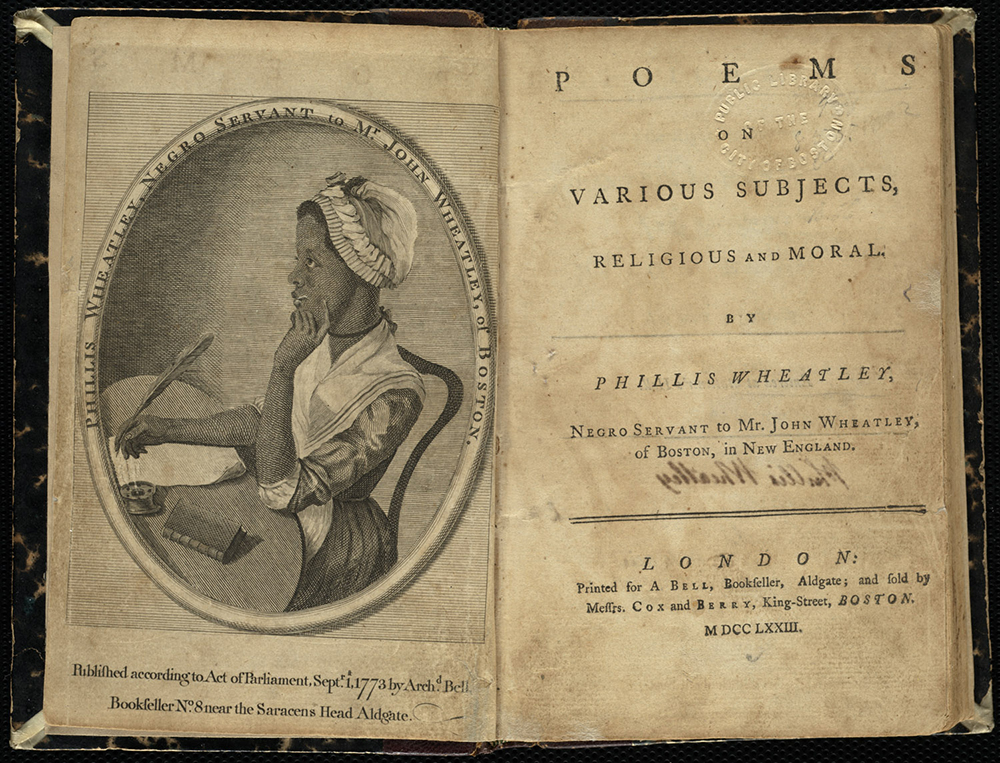

Until theBelindabook cover, the paintings I encountered in college and graduate school that featured black figures were as limited and repetitive as the few black writers assigned. The only British Romantic-era text I was assigned that featured a black figure on the cover wasThe Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano,which tells of his enslavement in childhood , after being kidnapped from his Igbo village and transported to Barbados, and buying his freedom. The covers of his autobiography usually feature one of two portrait images: a portrait by Daniel Orme that probably featuresEquianoand one that is probably Ignatius Sancho, born on a slave ship around 1729 and painted by Thomas Gainsborough in 1768. The men are interchangeable as a stock black figure. Similarly, the etching ofPhillis Wheatleywas the only pre – twentieth-century depiction of a black female I knew as a student. Digitization of museum collections and exhibits that focus exclusively on race and portraiture have pulled me more deeply into a broader study of Romantic-era portraiture and how it reflect and contributed to England’s abolitionist movements; as I work out a coherent narrative for these paintings, seeing the attendant required me to step back and think of black women in portraits before and beyond abolitionist debates.

When I went to see the painting again one fall afternoon a few months after the party, Appiah and I wound up having a wide-ranging conversation during my visit. He told me about different pieces in the apartment (the first portrait he showed me was a gift from his mother), and we talked about the technical and political aspects of the painting of the duchess — representing dark skin on canvas, the way that race and status are at play in its composition, the temporal and spatial geography that underscores how black figures appear in art. We discussed what identity means when it comes to unnamed figures in art and what they suggest about what black studies scholar and humanities professor Christina Sharpe calls “the asterisked histories of slavery, of property, of thingification, and their afterlives” in her bookIn the Wake: On Blackness and Being. What this has meant for me is working out what narratives about black figures in England emerge once we move beyond token images.

Visiting the Yale British Museum of Art’s 2014 exhibitionFigures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britaintransformed what had been mild curiosity into a more urgent set of questions. I was puzzled and mostly amused when Broadview Press’s 2002 edition ofEmily Brontë‘sWuthering Heightsarrived with a Moor on the cover — not the desolate landscape I’d been accustomed to since first reading the book in high school but an actual black figure. The 2008 Broadview edition of the anonymously authoredThe Woman of Color: A Tale, edited by Lyndon J. Dominique, has a woman of color on the cover, but I was so fascinated by the story that it didn’t register as significant. The Yale exhibit, however, included portraits, busts, books, and other artifacts showing that, rather than a painting here or there, there was an entire universe of black figures that, when taken together, tell a story about Britain, protest, taste , and gender politics. The attendant with her self-possessed pose and gaze fits into that world.

The Attendantwould have been painted in the mid-seventeenth century, before the abolitionist debates in Britain were gathering strength. The attendant’s gaze and self-possession are very different from that of other portraits I’ve seen of black figures with white figures. Take the black woman in the 1760 s portrait of Lady Elizabeth Keppel painted by Edward Fisher after Sir Joshua Reynolds. In this portrait the black figure is kneeling in much the same way as the black girl offering the duchess pearls in the National Portrait Gallery painting. Here the offering is a garland, with Keppel positioned between the black figure and a statue of Hymen, the god of marriage. The curatornotesthat Fisher lists the black woman simply as “negro” and that the presence of Hymen reminds the viewer that Keppel was a bridesmaid in the wedding of George III and Charlotte. I first saw the portrait in Amma Asante’s 2013 filmBelle, about the nieces of the famous judge William Murray, 1st earl of Mansfield, and the different paths they take to marriage. (Critic Wesley Morrisdescribedthe film as “California rollJane Austen, a class drama loaded with political and romantic filler. ”) Belle sees the painting early in the movie, and it foreshadows her particular marital conundrum. As Mansfield’s niece, she is expected to marry a member of the gentry, but as a woman of color, she is less socially appealing than her white cousin to the men in their social set. Her explanation of what marriage means to women brings to mind how white women likeMary Wollstonecraftcompared the institution to slavery. “It seems silly — like a free negro who begs for a master,” Belle tells her suitor. The analogy works for her because she is Mansfield’s niece and possesses an inheritance from her white father. The composition of the painting is a reminder of a more common fate for black women. The white figure’s proximity to Hymen in the painting affirms her connection to marriage, a complicated institution for the black woman at her feet. Despite the opulence of the black figure’s clothing (the curatorial note explains the dress might have been a hand-me-down), marriage for the black woman either would have been denied outright or, as it was later in the West Indies, promulgated as a way to extend enslavement in the years up to and immediately following the 1807 Act of Parliament abolishing the transatlantic slave trade in the British Empire.

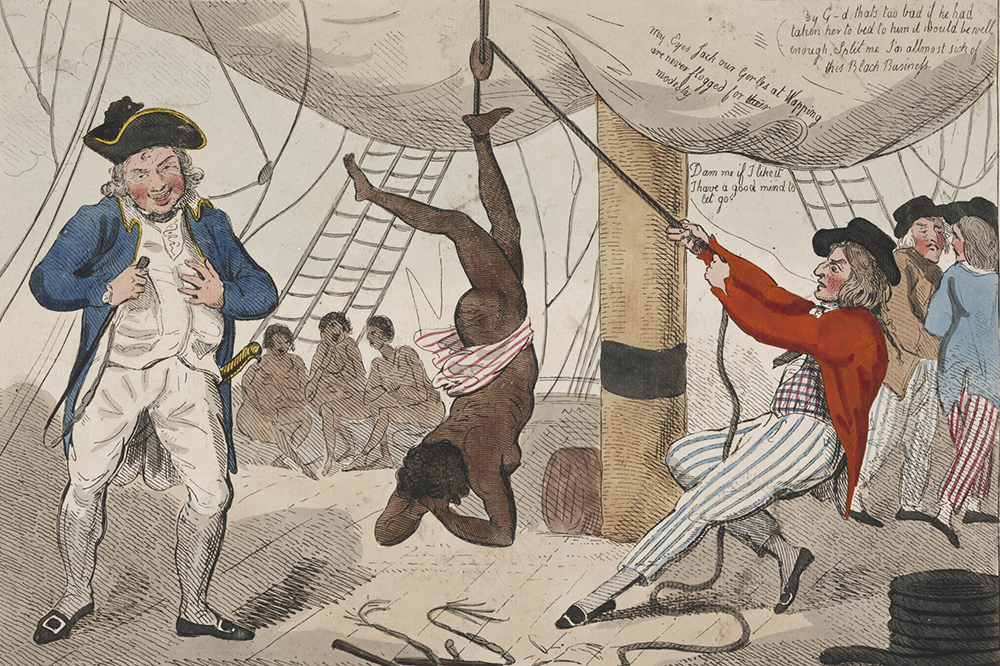

Yet both the attendant and the black woman in Fisher’s painting are depicted with more dignity than black women in etchings circulating in the late eighteenth century as the call for abolition increased in urgency. In Scottish caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank’s violent and satirical 1792 printThe Abolition of the Slave Trade, the black woman at the center of the sketch is on a ship, suspended upside down and nearly nude with a cloth doing little to offer her modesty, while three nude black women huddle together at the back of the ship.

In the late 1790 s,William Blakeillustrated John Stedman’sNarrative of a Five Years’ Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname, from the Year 1772 – 1777, Elucidating the History of That Country and Describing Its Productionswithengravings, including one titledFlagellation of a Female Samboe Slave, that were so graphic and violent that eighteenth-century readers considered the book an antislavery treatise. The depictions of black women in these paintings are never neutral, either showing them in service to individuals (in the genteel portraits) or toward explicitly political ends (in the violent etchings).

Stedman’sNarrativeincludes the story of Johanna, which also was published separately asNarrative of Joanna, an Emancipated Slave. Blake illustrated her with one breast bared, far removed from explicit scenes of violence; the image is closer in tone to the illustrations in Maria Edgeworth’s 1804 short-story collectionPopular Tales. This collection of didactic stories, written for young people, walks a careful line between teaching virtue without telling too much about vice. It includes a story called “The Grateful Negro” whose politics about subduing enslaved people with empty mercy is offensive to twenty-first-century readers and whose clunky, didactic prose must have chafed at the good taste of any nineteenth-century reader. A graduate professor gave me a late nineteenth-century edition of the stories printed by Cox Brothers and Wyman Printers in London. It includes an illustration of a scene featuring Clara, a black woman, tending to Caesar, the titular grateful negro who wants to marry her. She is presented in a domestic tableau that suggests that, despite her skin color and status, she is like many an ideal Englishwoman — compassionate, competent, and responsible for a peaceful home.

In 1826 Amelia Opie wrote about the horrors of sugar production in her poem “The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar. ”The verse also was intended for children:“ Who dares an English peasant flog?… Who sheds his blood? treats him like a dog? ”Illustrations accompanying the poem depict enslaved women and men working side by side in sugar production, but Opie’s lines bring to mind a 1725 painting in the Yale exhibit of an elegantly attired girl in a garden with a dog and a person of color that was originally titledA Young Girl with a Dog and a Page. Pointing out that the dog and the “page” wear the same collar, the curatorslistthe title asA Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog. They not only correctly identify the page as enslaved (the collar would have been locked with a key held by someone else) but change the order so that the human is listed before the animal. The composition is familiar: both the enslaved man and the dog are staring at the young, white girl.

The most notable exception to such depictions is the painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle next to her cousin Elizabeth Murray, attributed to David Martin. These two women stand side by side as peers, both beautiful and both beautifully attired. This painting inspiredBelle, the saccharine period romance that not only places the responsibility of the abolitionist movements on the shoulders of a woman of color behaving perfectly in every scene but also makes it seem like black and white women faced comparable obstacles to marital bliss in the eighteenth century. They didn’t, but Dido’s place in the Mansfield household is reflected by the agency the artist captures in the painting of her.

If the duchess ’attendant is looking off in the distance, Dido Elizabeth Belle is staring right at the viewer. It seems as if something or someone has amused her. And yet the artist (originally thought to be Zoffany) connects her to a world different than the one she was raised in, one that her cousin safely enjoys. While it’s true that Dido, the daughter of Royal Navy officer John Lindsay Murray and the enslaved Maria Belle, is standing next to her white cousin, looking at the viewer, she remains tied to the legacy of her mother’s position. She is wearing a turban with a feather and carrying a basket of fruit, a reminder that, although she has been raised in Britain as an heiress and a gentlewoman, she remains connected to labor. Her cousin, with flowers in her hair, is simply holding a book, a sign of leisure and not industry in the eighteenth century.

Across from the attendant and the duchess, Appiah and Field have placedPortrait of a Gentleman with a Young Servant, a painting from the late 1730 s attributed to Charles Phillips. The servant, a young man of color, is standing next to someone who, according to Appiah, might be Sir George Thomas, a governor of the Leeward Islands in the eighteenth century. The attendant on the other side of the room is black, but Appiah pointed out the young man in this painting could be Indian. Neither the attendant nor the servant is identified except by their skin color and status. We don’t know their names. Of course, names for black people were fluid — given, assigned, and reassigned for the convenience of those they were forced to serve — and their place in society would have been even more unstable. Appiah and I were less interested in the portrait’s primary figure than we were in the young man who probably made the trip with him from the Leeward Islands to England. The young man’s fate inevitably would change after the moment trapped in the suspended reality of paint. Sir Thomas would die, and the servant would be listed as property to be inherited, sold, or sent someone else. “People have to rediscover who they are,” Appiah said pointedly.

Working to make sense of asterisked lives represented in these paintings is not about discovery and rediscovery; looking backward at the various ways that black female figures circulate and are put to use is more than just filling in some gap in our understanding of the period. It also teaches us how we view the use of black figures today. It teaches what to see and how to read it. When I saw the attendant the first time, I was leaving the party. She stopped me, and I uttered some word of surprise. The second time I saw her, I asked Appiah if other visitors had asked about her. I’m always curious to know if other people see black figures who are clearly present but often ignored. He said they hadn’t, and we agreed that it might be because of where the viewer needs to be situated in order to even notice her. “You see her,” Appiah said, “when you get there.”

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings